Nearly one year after the release of a community consultation report, Indigenous faculty and students reflect on Ryerson’s progress with Indigenous reconciliation, and its shortcomings

WORDS BY LINSEY RASCHKOWAN

ILLUSTRATION BY SAMANTHA MOYA

***

On any given school day, Emma Cooper will wake up in her home in downtown Toronto, and smudge herself with sage. Although she owns all four sacred medicines—sage, cedar, sweetgrass and tobacco—sage is the one she primarily uses in order to cleanse negative energy.

Cooper, who’s majoring in creative industries at Ryerson, does this morning routine every day. After getting ready, she walks to school, where she passes the statue of Egerton Ryerson, the university’s namesake. “Walking past that statue every day is really hard. It sucks,” says Cooper, a member of the Lenape and Delaware tribe from Six Nations, while sitting in the Oakham Café in eye’s view of the statue. Her fingers, adorned with vintage rings from Tribal Rhythm, are wrapped around a cup of tea.

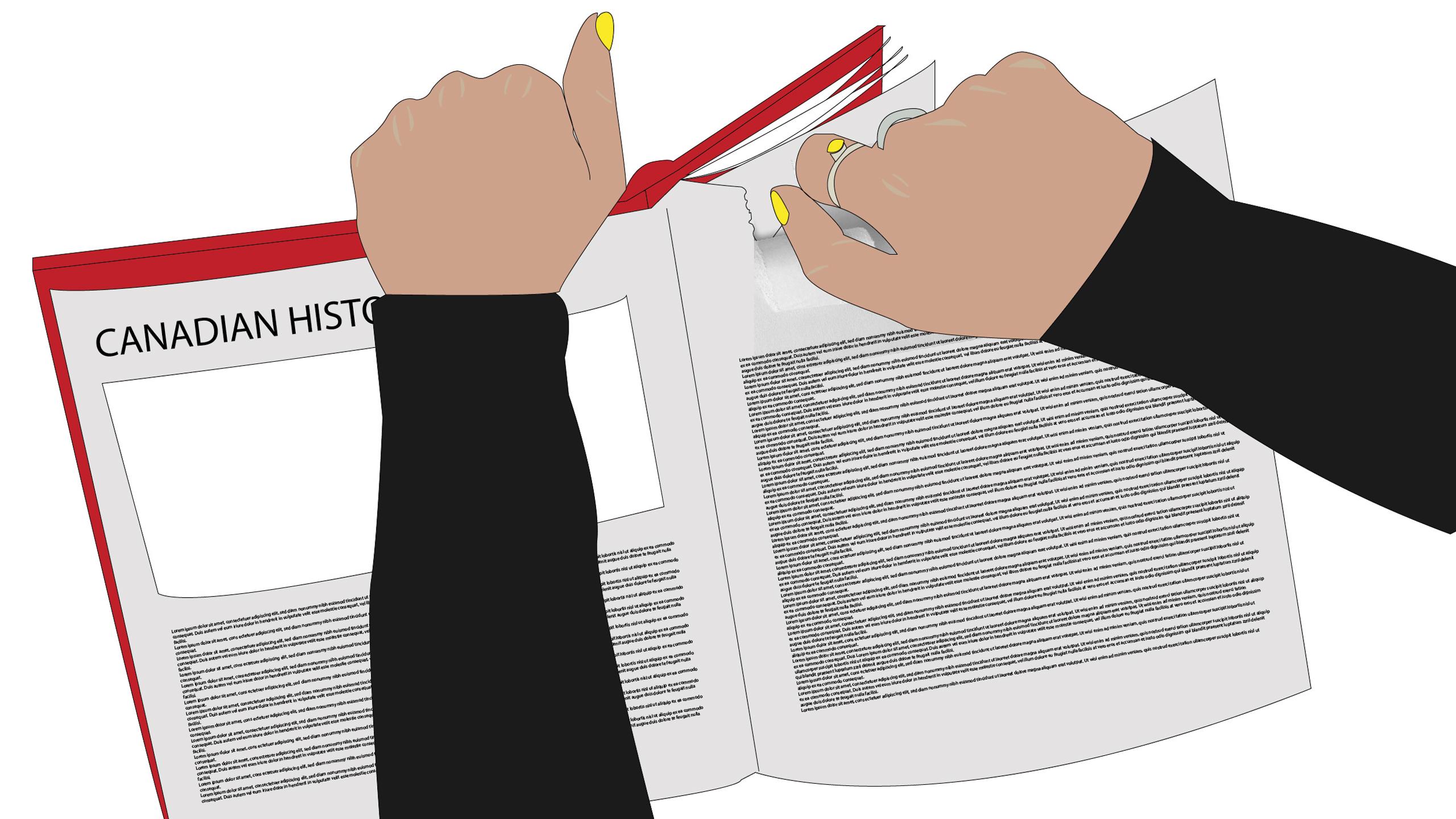

Egerton Ryerson, aside from founding the school, is known for contributing to the creation of the residential school system, where Indigenous children were taken from their families and forced to assimilate into white culture. The system operated in Canada for more than 100 years, during which time thousands of children were dying at alarming rates. The last school did not close in Canada until 1996, and according to a 2016 report from Statistics Canada, the genocide continues today with The Millennium Scoop. Indigenous children account for more than half of the children in Canada’s foster care system, despite First Nations, Métis and Inuit youth making up just eight per cent of the age group nationally.

Education systems in Canada have reflected this history, and Ryerson is no exception. The debate over the still-standing statue prevails today. Cooper laughs uncomfortably, mentioning the plaque that was placed in front of the statue earlier this year as a result of the reconciliation process. Part of it reads:

“This plaque serves as a reminder of Ryerson University’s commitment to moving forward in the spirit of truth and reconciliation. Egerton Ryerson is widely known for his contributions to Ontario’s public educational system. As Chief Superintendent of Education, Ryerson’s recommendations were instrumental in the design and implementation of the Indian Residential School System.”

Back in April, Denise O’Neil Green, Ryerson’s vice-president equity and community inclusion, discussed the possibility of removing the statue with three Indigenous students, who shared their concerns about leaving it up. “However, at this time there are no plans to remove the statue,” she wrote in a statement. It’s been one of many issues preventing the school’s reconciliation with its Indigenous community.

In January, a community consultation report was released that outlines what Ryerson has worked on, and what it will work on, to “strategically move forward together” toward reconciliation, providing themes such as “Indigenizing” the university by incorporating language courses and relevant community-related issues, as well as “symbolic gestures,” including formal apologies. It also highlights the goal to double the number of Indigenous faculty.

But now, nearly 11 months after the consultation report’s release, some Ryerson students and faculty are reflecting on the school’s progress. Many of the efforts and the goals they are attempting to achieve are within the academic landscape, a key component in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. But these efforts, while present and behind-the-scenes, don’t feel substantive to some due to their lack of visibility, particularly for students such as Cooper.

***

Cooper was lucky to have experiences at Ryerson that relate to her culture, but only because she sought them out herself—for her, it was her Indigenous Media course she took through creative industries. The course looks at Indigenous art through screenings, readings and guest artists, and examines two-spirit, gender, class and race issues through the lens of Indigenous artists. But it’s an RTA course that isn’t mandatory in her program, so most students won’t come across this content unless they actively seek it.

The course was created roughly five years ago by Dr. Lila Pine, a new media artist of Mi’gmaw ancestry from the Bras d’Or First Nation. Pine, who is active in the restoration of Indigeneity in language and cross-cultural communication, is also the director of Saagajiwe, which is the centre for Indigenous arts (formerly known as the Indigenous Communication and Design Network), part of the Faculty of Communications and Design. It’s set to be located in the Rogers Communications Centre. The centre made a callout for an Indigenous artist to design the entrance of the centre. The project, with a budget of $15,000, is set to complete this December. Centres like these can provide spaces for students to engage with and learn about their culture.

But while visual presence of Indigeneity on campus also needs work, the Indigenous Media course in itself can provide a safe space to speak about Indigenous issues. Right now, Cooper’s culture is not reflected in her mandatory courses. While just an optional elective to most, the class was a safe space for her to discuss Indigenous issues in the media—including her frustrations on the statue debate.

She had stopped smudging for a while, too, but the course brought her back to it. “I’ll smudge before I do anything,” she says, describing it as a healing process after a bad day. The course has been called “ahead of its time,” but now, it’s one of the most popular courses, according to dean of FCAD Charles Falzon.

While there’s a push to increase Indigenous content in FCAD’s programs, the focus has been on making more role models for its students, through bringing guest speakers and artists. Falzon said these guests can become mentors for those students, and adds the faculty is working to create job opportunities for students by showcasing their artwork to companies looking to hire.

FCAD is also beginning to include Indigenous content into their existing courses. In the fashion program, for example, one of the mandatory first-year courses covers Indigenous fashion, and the school has an Indigenous artist in-residence. But the dean knows these efforts don’t satisfy the requirements for reconciliation.

“Look, it is 100 per cent promising and optimistic. Is it enough? Not at all,” he says. Regardless, he says building foundations is an important step.

***

Nika Zolfaghari is an enrichment and outreach coordinator representative for the faculty of engineering and architectural science. In her office in the George Vari Engineering and Computing Centre, she rifles through papers and folders, and finally comes across a page with a graphic about the percentage of Indigenous students and staff at the school. The number is low.

Science is often forgotten in the discourse around systemic racism and its impact on our current colonialistic understanding of the world. According to the Understanding Racism report, published in 2013 by the National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health, “the practice, discourse and culture of western science are based on, and therefore reinforce, racist ideologies and structures.” Due to the colonial system that provided the education system we have today, only western science had the resources to research what would eventually lead to “hypothetical racial differences.”

Science is an inherent part of First Nations culture. Amber Sandy, the Indigenous knowledge and science outreach coordinator, points out that all of their stories have aspects of science in them that teach about the relationships between different species, the environment and the people, and how we must care for these things. Rooted in Indigenous knowledge and learnings is a very holistic sense of curiosity. She says we’re all born curious. At the outreach camps and events the science faculty holds for potential students, they often have Indigenous speakers at the panel to discuss that form of scientific knowledge.

When David Cramb, dean of Ryerson’s Faculty of Science, lived in Calgary, he used to meet with a Dene elder on a regular basis. He was told a story about a giant beaver that was being chased around the land, then hid, and decided to become a mountain.

“There’s this traditional beaver mountain thing up near Fort Chipewyan, and I was like, ‘Oh man, that is such a great story, but come on, a giant beaver? Please.’”

Three weeks later, Cramb found out through the CBC that an archaeological dig near the mountain actually found giant beaver bones. Seated across from Cramb, Sandy laughs and says, “Yes, we’ve been telling you that for years.”

Sandy finds experiences of that nature fascinating: “It [opens] your eyes a little bit to show you that there’s a lot of value in this knowledge.”

Including storytelling in scientific studies is one of the ways they are planning to incorporate Indigenous knowledge into the programs.

As for Zolfaghari, she is currently working on ways to include Indigenous issues in the program, such as waste water management on reserves or designing infrastructure from an Indigenous perspective. This includes changing the way content is taught in the courses within the faculty and making it more inclusive to all identities.

But one thing she says needs to be a fundamental focus to reconciliation is the student population. “We don’t have very many Indigenous students, period,” she says. “So one of our biggest priorities to begin with, is increasing the number of Indigenous students we have within our faculty.”

According to the 2015-16 Employee Diversity Self ID Report, in 2016, one per cent of Ryerson employees, and two per cent of Ryerson students, self-identified as Indigenous. In 2016, zero per cent of staff hires identified as Indigenous. Zolfaghari wants that percentage to mirror the Indigenous population of Canada, which in 2016 was 4.9 per cent of the population.

To increase the population, outreach programs take place by having the school visit high schools and elementary schools, and hosting camps and events for youth to engage in engineering and science through hands-on activities. It’s a tool used to show young students the variety involved in the programs, from chemical engineering to architectural engineering to sound engineering, among others, while raising awareness for Indigenous initiatives.

Through her outreach position, Sandy says she is also working to aid any incoming students as well as any current Indigenous students in finding careers in the field. Sandy’s creating a position for students, saying she will “have a career boost position” to hire a student for the coming year, to do work on programming—even though she says she’s only aware of one Indigenous student in the entire faculty.

But outreach programs don’t do very much for the current students at Ryerson, and the committee doesn’t have anything planned to create resources for the students as of yet.

While Ryerson’s efforts are noteworthy, Cramb and Sandy say the concept of “Indigenizing” campus needs reconsidering. Instead of looking at our existing understanding of things with an overall Indigenous lens, the better method would be acknowledging Indigenous culture and history that played a role in what we know. “Our knowledges, and everything, are standalone,” Sandy says.

“Just considering the word ‘Indigenizing,’ and making it be a part of it is really problematic, because then you’re getting into exactly what colonization has succeeded in doing.”

Cramb agrees and notices colonialist tendencies in universities’ efforts to “Indigenize” their schools. He says we should focus on speaking and listening to elders, something he’s done during his time teaching in Calgary.

***

Hilary Lafleur is a third-year Métis student from the Painted Feather Woodland tribe in Ontario, currently studying business management at the Ted Rogers School of Management. She’s attempted in the past to find student support, but due to a heavy course load, it’s difficult for her to find them. Due to their invisibility, she’s never had much luck. The university does have some resources available, but they’re inaccessible to students like Lafleur. It creates a barrier in her education. She had been studying at Ryerson for three years before she found out about Ryerson Aboriginal Student Services (RASS).

Resources on campus specific to Indigenous students exist, but they’re not all designed to provide student support, and they’re not all from Ryerson either. The Indigenous Students Association, Ryerson & First Nations Technical Institute and RASS are designed more specifically for student support.

Brian Norton, RASS’ program coordinator, says the service reaches out, usually through email, to Indigenous students even before they begin their studies at Ryerson. This means letting the students know about what RASS offers, including financial and academic advisement, traditional counselling, academic counselling and bringing awareness to the different events that are held for Indigenous students throughout the year.

But Lafleur and Cooper agree that finding resources can be difficult, and it’s often left to the individual to find their own way.

This could be due to the fact that this year, RASS is understaffed. The student liaison officer is away on sick leave for the year, and the student support advisor left her position in August to pursue a PhD program.

“We are very short-staffed for the critical time when students are coming in,” says Norton. RASS is working to remedy the situation by hiring new staff, but have been leaning on peer support for outreach and communication with students, for the time being. This is probably the reason why students like Lafleur say the resources escaped her. “I would have no idea there were resources of any kind,” she says.

***

Cooper stopped hoping for any eventual, symbolic removal of the statue. The whole debacle feels similar to how Cooper feels about other Indigenous issues on her campus: “No matter how much we talk about it, no matter how much a fuss we make, it’s like fighting a brick wall,” says Cooper. “A lot of it is just talk.”

Now, she’s focusing on her music career. She practices guitar nearly every day and interned at Universal Studios this past summer. She writes her own music, but usually prefers to perform covers. Once a year, the program holds a coffee house set on Ryerson campus, where Cooper performs. Eventually, if she starts performing her own songs frequently, she hopes through this art she can create more space for her Indigenous culture.

“If I ever have a platform,” she says, “Indigenous issues is what it would be for.”

In 2016, Kathleen Wynne promised to teach the legacy of residential schools throughout Ontario schools. However, as of early July of this year, the provincial government, now held by Premier Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives, cancelled the curriculum rewriting sessions, which would have included Indigenous content. If they had taken place, they would have accomplished teachings on residential schools and the genocide from colonialism.

That revised curriculum would have taught the Canadian history Cooper’s known about since she was a little girl. “Growing up knowing about that stuff is frustrating,” says Cooper. “How can no one else know about this?”

Leave a Reply