Students at the Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing highlight issues of transparency, communication and meaningful support.

Words by Charlize Alcaraz and Dhriti Gupta

Visuals by Harry Clarke

Sitting cross-legged in the middle of her bed in her Toronto apartment, tears streamed down Ann Mikayla Estrella’s face while on a phone call with her dad, who was thousands of miles away in Saudi Arabia. Estrella was trying to enroll in a mandatory sociology elective to no avail—not one of the 10 different available sections in the class fit her schedule.

With no solutions from the administrators she’d reached out to for help, she’d have to take the course during summer school with increased international student fees. This was the last straw.

Last December, the second-year Ryerson nursing student had called her dad to talk about how she wanted to change career paths because nursing didn’t feel right for her anymore. Growing up, she had always wanted to help people, but after pouring $60,000 of international student tuition into the program, she didn’t feel like she could fulfill that goal through Ryerson’s program.

“Why did I come to school here? Why am I in Canada?” she asked her dad through sobs. “I want to switch programs.”

This wasn’t the first time that Estrella felt let down by her program administration. When a close family friend passed away this semester, Estrella couldn’t focus on any of her school work. She had a paper due for her Concepts, Individual and Family class that discussed topics surrounding family, death and grief; she needed an extension to take her time and process her own loss.

She didn’t realize this would create more trouble for her. Her request for an extension was rejected twice by her nursing professor and Ryerson’s Academic Accommodation Support (AAS). It took her more than a week to receive an extension on the grounds of bereavement and she had to talk to her professor, year lead, associate director and an AAS facilitator to get it.

She feels like support is confusing to access because of program-wide miscommunication; something that’s soured her experience with the Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing right from the beginning of her degree.

“Nursing is a profession where people need to be very organized. Why is [our program] a complete mess?” she asked. “Who’s caring for nursing students?”

With an admission grade range of 90 to 93 per cent, Ryerson University offers one of the most competitive nursing programs in Ontario. Last year, the program saw over 4,500 applications in total between Ryerson and the collaborative programs at George Brown College and Centennial College, with only 560 spots available across all three schools, director of admissions Mike Emery says.

Known as one of the most academically challenging programs at the university, Ryerson nursing students say the program isn’t built for them to succeed. Some say they’ve endured years of fatiguing workloads, high expectations and mental health problems—all with little support. Students describe a lack of accountability and communication within the program as well as unnecessary struggles to obtain a degree that’s meant to help them take care of others.

By the time these students graduate, some have already fallen out of love with the discipline.

Nursing requires people to hold themselves to professional responsibilities from day one, says Sally Thorne, a nursing professor at the University of British Columbia and editor-in-chief of the journal Nursing Inquiry. Because of this, she says nursing education is more than just taking university courses—it’s also dependent on the acquisition of complex skills and socialization into a role that holds public trust.

“It’s not simply learning facts in nursing school, it’s an awful lot of supporting people as people to become the professional that they want to be.”

The Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing says they’re doing the best to support students within the newfound limitations of the pandemic.

Over the past month, they’ve sent out messaging via social media and email about mental health, financial and counselling support that students can access either within their program or as a Ryerson student in general. The school also offers a grant for students in financial need to be able to commute to their clinical placements, pledged to match student-led fundraising to support fellow students up to $50,000 and held frequent town hall meetings to address confusion and uncertainty.

They’ve also invested about $500,000 in virtual simulation as well as the hiring of extra instructors to account for reduced clinical group sizes due to social distancing.

“We understand that during these challenging times, the resulting solutions may not meet the expectations of all students,” said a spokesperson for the Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing in an email to The Eyeopener in January.

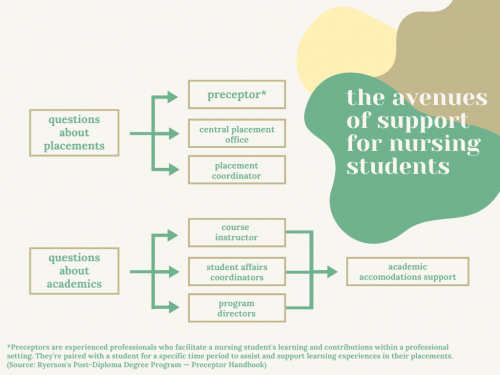

“We have encouraged…students to engage with their faculty advisors, leads for courses, year leads, associate directors and the directors for informed answers to their questions and concerns,” the email reads.

But some students claim the school’s efforts aren’t enough and weren’t enough, even before the pandemic started.

t wasn’t even 5 a.m. when Emma Murdoch trekked alone to her bus stop, fighting against the biting wind. Surrounded by darkness, her frozen fingers clenched her keys in one hand and dog spray in the other. She felt lifeless, exhausted from the long hours she put in at her part-time job after school to support her early morning commutes to get to a placement that didn’t align with her interests.

Before she could reach the stop though, she watched in disbelief as the first of the two night buses she needed to board to reach her clinical placement by 6:30 am rumbled right past her. The subways weren’t open yet and she’d have to wait 25 minutes for the next bus, causing Murdoch to miss her transfer as well. Every bus ride she took for that placement, she’d find herself contemplating: “Can I even do this? Is this what nursing is like? Is this even worth it?”

On top of her placement not being in a maternal or surgical-based area of nursing—what she wanted to pursue in her career—Murdoch felt as though it wasn’t appropriate for a fourth-year student. While she was able to practice foundational nursing skills like catheter placements, bed-making and feeding, they were just that: repetitive “cookie-cutter” skills. Instead, fourth-year students should ideally be given a chance to take all the knowledge they’ve developed in previous years and put them into their practice, says Murdoch.

“Sometimes you have to do placement you don’t want to do and sometimes [it’s] the placements you don’t want to do that actually make you a better nurse,” she says. “But there wasn’t a lot of room to really critically think and develop yourself professionally.”

“Why am I working [hundreds of] hours…in a unit I’m not passionate about and that [won’t] really align with my career goals long term?”

Murdoch says it’s not uncommon for Ryerson students to get assigned to placements they don’t want. It’s rare they even get something within the top three choices they indicate in third year, she adds.

She says this comes down to the fact that between the main program and the collaborative programs, Ryerson accepts more nursing students than they can accommodate, creating a placement shortage. “That’s not the students’ fault,” Murdoch says. “We’re all fighting for the same placements.”

According to Thorne, placement shortages are a problem across Canada.

Nursing education is a joint responsibility between the healthcare system and universities, she says. Placements rely on either university instructors or nurses employed by health authorities to support and mentor nursing students in their placement setting.

For instructors, there are strict limits on how many students they can bring into a unit depending on the kind of health setting. And if a nurse paired to a student, also known as a preceptor, happens to get sick or resign, their placement would be affected. As well, the number of nurses in a unit who are able to take on the role of preceptorship is often limited.

“Those settings cannot manage very many students simultaneously,” says Thorne.

Either which way, she says university nursing programs are left in a difficult position when it comes to securing placements. This is only compounded by competition with other nursing programs and health professions for the same clinical placements.

As a solution, Thorne says there needs to be better unity and collaboration between the ministries of health and the ministries of education across all provinces.

“It would be a lot easier…if when you admitted 100 students to your program, there was already a commitment on the part of the local health authorities to be part of that process,” she says. “[They need] to be as actively engaged as the Ministry of Education…[in] committing to the support of those students.”

But Murdoch says besides increased placements, there are other ways the program could compensate for the skills their students aren’t obtaining. She says the program at Ryerson focuses on long-term care to a point where other areas of nursing fall to the wayside. For instance, there aren’t many pediatric or women’s health courses within the program to begin with, and during Murdoch’s time at Ryerson, they weren’t offered due to lack of funding.

She recognizes that the school tries to help with job applications by holding resume workshops and encouraging the development of transferable skills, but it just isn’t enough to land a job without experience.

“They’ve tried to help just in ways that didn’t actually help me,” she says. “There’s other ways they can help support us if they don’t have a placement…transferable skills don’t get you an interview.”

Taking matters into her own hands, Murdoch spoke to nurses within the field she wanted to enter and made a list of all the things she’d need to get hired. She ended up spending around $500 doing extra certifications in her final semester, without which she likely wouldn’t have gotten her current job, she says.

“It helps compensate for the fact that I don’t have 350 hours of experience in that unit as another student.”

She feels lucky to have been able to financially support herself through that but can imagine the frustration of others who can’t.

“You’re told you should be doing these things to market yourself and get better chances and it’s like, well, then why am I paying $7,000 for per year for a degree?”

The pressure that comes with constantly doing extra work on top of an already exhausting nursing education can also take a toll on students’ mental health.

Halfway through her degree, Jane Woods* was clinically diagnosed for anxiety and depression. On top of going over her professors’ powerpoint presentations and reading hundreds of pages from her textbook, Woods also had to watch hours of Khan Academy tutorials for her pathology class. She didn’t feel that the materials given to her by her professor really helped in her learning.

Further, due to the way the curriculum is structured, failing just one course can set students back by a year. If students on probation get a ‘C-’ or below in a nursing course, they’re required to withdraw from the program in its entirety with the possibility of applying for a reinstatement after one year.

Woods was experiencing unmanageable levels of burnout from her consistent efforts to succeed in her courses, and yet her grades were still taking a dip.

She says she was an ambitious student before getting into nursing, but when she reached her second year in the program, she felt a “significant loss of motivation or care for anything” and a “never-ending wave of melancholy and burden” from her depression.

“There was always a mountain of text to read or material to study every night on top of [clinical placements],” she says.

She found herself thinking, “Am I going to make it out of here alive?”

According to Douglas Levinson and Walter Nichols from Stanford University, “in most cases of depression, around 50 per cent of the cause is genetic and around 50 per cent is unrelated to genes.”

One of the non-genetic factors that increase risk of depression is severe life stress—something that’s all too common among university students.

According to a chapter in the book Health and Academic Achievement, careers in nursing, medicine and dentistry are demanding physically, intellectually and emotionally—especially for students who are “exposed to high levels of stress during their formation.”

After graduating in June 2020, Woods could only let out a sigh of relief when she finally held her mailed diploma in her hands.

“I was fighting every day for five years, and now the battle is over,” Woods says. “I didn’t feel victorious [after graduating], but I just felt like I [could] finally take a breather and never have to come back.”

arre Tsu went on winter break in December 2019 under the impression that her mandatory long-term care placement would be ready for her come January of the new year. She was wrong.

For two and a half months, she was passed from administrator to administrator, none of whom could tell her what was going on at the facility where she was supposed to be conducting her placement. It was one of the final requirements of her degree that she needed to graduate in the spring.

She didn’t understand why this was happening to her; she’d done everything by the book. She followed the CPO’s rule to not go looking for her own placement; emailed her preceptor after not hearing from them after Christmas; and followed up weekly with the CPO, her advisor and year lead.

Still, it was the end of last February by the time Tsu was finally able to start her placement. She had just six weeks rather than 12 to complete 290 hours of work on top of a full course load.

Tsu says she wasn’t alone in having a confusing experience with clinical placements. Many others in her year also started their placements weeks late due to widespread miscommunication and a lack of transparency about Ryerson’s shortage of placements.

Tsu says many were afraid to voice their concerns to the CPO for fear of being “blacklisted.” She says it was a commonly held fear that if a student complained about their situation, they would be given poor placement opportunities later on.

“There’s always a lot of conspiracy among students…because you’re not getting one [straight] answer from wherever you’re supposed to get answers from,” she says.

Tsu says that consequences of this lack of communication became evident when the pandemic hit and new nursing graduates were needed in the workforce to combat COVID-19.

Last March, the College of Nurses of Ontario (CNO) authorized the emergency assignment class to register new nurses to assist during a province-wide health crisis, like the pandemic. That meant for 60 days or more, Tsu and her classmates could potentially cover positions vacated by regular nurses who were redeployed or contribute to COVID-19 relief efforts, under a Registered Nurse license.

To take part, new graduates like Tsu needed proof of their nursing education—something Ryerson was responsible for sending over to the CNO. The same proof was required for students to book their National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX), the test that has to be taken by all nurses across Canada and the U.S. for them to practice under a regular general class licence.

The proof of education took months to get to the CNO. Students were patient at first, understanding the instability and delays that the pandemic brought along with it. But as one-on-one emails were exchanged to try and understand the delay, “confusion started to take root,” Tsu says. Students were hearing that other schools had already sent proof to the CNO.

Only when Tsu sent an email on behalf of her cohort requesting a faculty email explaining what was going on did they get an apology and a ballpark estimate of May 14-16 for when the list would be sent.

But Tsu says it wasn’t sent until June, preventing hundreds of qualified nursing students from entering the workforce to fill an increased need during the pandemic.

“Ryerson is producing the largest amount of [registered nurses] in Ontario and the emergency class was created during this time to literally force this cohort of nursing graduates…into the workforce,” she says. “So it really frustrated me that they didn’t understand…the urgency for us to get this eligibility.”

Ryerson did not respond to The Eye’s request for comment regarding the delay.

Out of the 816 nurses registered under the emergency assignment class last year, 82 per cent had recently graduated from Ontario’s nursing programs, according to a spokesperson for the CNO.

Thorne says nursing graduates and students have “been playing an enormous role across the country and across the world” in combating COVID-19, especially given health services have been overwhelmed in trying to reorganize their services and set up safety measures to protect patients, family and staff.

Pending graduation, Tsu says that a lot of her peers already had jobs lined up, including herself. The gravity of the situation became more severe as they needed to write and pass NCLEX before they started their employment.

“It’d be more forgivable if we were a cohort of 50….but we’re the largest nursing program in Ontario so this [meant] 500 plus RNs; out of work, no use.”

n her current job in the labour and delivery (L&D) unit at Mount Sinai Hospital, Murdoch’s colleagues know her as a cheerful and passionate nurse. And she is—she gets to wake up every day to go to her dream job that she loves.

For Murdoch, it’s odd to remember how just a year ago she hated nursing and how many times she contemplated dropping out as she waited for her bus in the snow or rain. In her unit, she’s one of the only Ryerson grads and her colleagues are always surprised to hear about her alma mater, since Ryerson students aren’t really known to have experience in the area of L&D. Murdoch knows it was the networking and extra work she did on her own time that got her the position.

“I think students will always end up successfully achieving their goals,” she says. “But I didn’t achieve my goals because of Ryerson…and I think that’s an issue.”

Woods says that her time at Ryerson wasn’t all bad; there were bright moments thanks to the good friends and professors who helped her along the way. They made her realize that kindness goes a long way in nursing, something that she tries to exercise towards other students.

Now a hired registered nurse, Woods helps current nursing students in making their studies a bit more tolerable. She’s joined several student Facebook groups to guide them towards finding a job at the hospital they want to work at and let them know what sort of interview questions to prepare for.

“As competitive as nursing is, there’s always space to be kind and always space to be supportive.”

She says that while compassion, empathy, patience and trust are driven into students as core tenets of nursing right from first year, it’s important that the school provide that for the students as well.

“We want to be understanding and we want to just be able to go out and serve the community and help people,” she says. “Why aren’t we receiving that same kind of support?”

*Name has been changed to protect source’s privacy and employment.

Tanveer

Thanks for shedding light on the truth.